Embroidering memory: bringing the Szopka to Krakow’s Main Square

© Małgorzaty Samborskiej

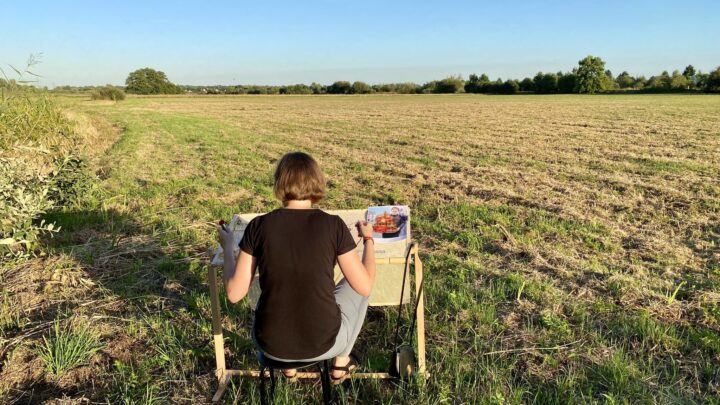

Memory is a fascinating and ephemeral matter: we keep attempting to capture, order, preserve it. My art asks questions pertaining to the way we remember things and what memories really are, especially in times when an excess of images seems to distort our perception of reality.

My artwork

My artwork focuses on memory: the way it works, records the past, and the things it leaves within us. I ask the question: what could be preserved and how does the past reappear. Every single day we take 4.7 billion photos globally. Facing such an abundance of images, is photography still a good carrier of memory and tradition? Or perhaps the things we genuinely remember come to our minds as a vague, blurry image when we close our eyes? An image that is imprecise, yet bursting with emotions, one that can be felt deeply.

In family memories and in cultural traditions, we strive to preserve what's important, to pass it on to future generations. In my work, I cross stitch photographs from family albums, overheard catchphrases or loved ones’ words of advice, blending them with colourful threads and fabrics that become a carrier to convey the warmth of memories.

About the technique

Widely popular in Poland, cross stitching is usually associated with landscapes, flowers, or genre art. In this project, I sought to uncover its other meaning (different to the decorative one), by stitching a picture of a nativity scene’s creator ‘pixelated’ by crosses. Here, a stitched cross becomes a metaphor for a digital pixel.

© Małgorzaty Samborskiej

Starting point

While working on the Szopka project, I looked at photographs from the Museum of Krakow’s archive, wondering how, in 100 years’ time from now, someone could research the tradition of Krakow nativity scene making. The first thing that comes up are photos from the finale of the annual Krakow Nativity Scene Contest. So, above all, the ultimate result of the tedious work of nativity scene makers that often takes many months to complete.

Though I’ve been familiar with the tradition and the contest itself for years, there was one detail that I had previously missed and that only now caught my attention. Namely, a vast majority of completed nativity scenes are brought to the contest in the Krakow Main Square by the creators themselves, carried in their hands.

Particularly this gesture of ‘bringing one’s Szopka to the Krakow Main Square’ became the starting point for my embroidery creation.

In the media representation, during the exhibitions, nativity scenes are usually photographed without their creators. And after all, they are the ones who create them year after year with their own hands. The gesture of holding the nativity scene in your hands, one that is intuitive and tender, one that stems from its fragile and delicate structure, expresses gratitude and respect for cultural heritage protected by nativity scene makers.

The photograph for this embroidery project was selected with the help of the Museum of Krakow’s team. It presents Mr Wiesław Barczewski, a mechanical engineer and organist who has participated in the Contest since 1980, with Saint Mary's Basilica visible in the background. Mr Barczewski specialises in small and miniature nativity scenes. Even the British Royal Family have one. It perfectly embodies the spirit of this living heritage.

© Małgorzaty Samborskiej

A reflection on memory

The main idea of my project is the reflection on the functioning of memory in the age of overproduction of photography. How do we remember? How do we memorise historical events? What do traditions look like in our memory?

Increasingly more (if not most?) of our own memories, in fact, draw upon photographs. We remember some experiences and events as they are brought to us via images that have been multiplied in the media. Therefore, the ‘pixelated’ nature of a stitched photograph seems to me an apt metaphor of what we really manage to imagine as memories.

Here, a stitched cross becomes a metaphor of a digital pixel, and from an even wider perspective, a symbol of our memory’s ‘low resolution’. The closer we come, the more elusive the picture. However, if we attempt to look at it from a certain distance and perspective, we see more.